Major changes loom on the horizon for postsecondary distance education programs in the United States, but we are now in a temporary limbo of uncertainty. The Department of Education’s Program Integrity and Institutional Quality negotiated rulemaking sessions ended on March 7. Despite tons of suggestions and hours of discussion, none of the distance and digital education issues reached “consensus” among the negotiators. That leaves the Department with the responsibility of writing proposed rules. What will they do?

Today’s post is a brief update on the proposals considered and discussions that occurred in the third and final week of negotiations. For context, please review our summaries of the week 1 and week 2 sessions.

During negotiations, the Department’s proposals seemed bearish on distance and digital education. They want to see change.

Just because the proposals are going into hibernation, don’t sleep on them now. We encourage you to stay alert as the changes proposed could have a major impact on distance education and all of higher education. And remember, the Department can now write whatever language it wishes to propose and is not tied to the proposed language from week three. Final language could become less or more restrictive.

In the coming weeks, we will publish a follow-up post with a “call to action” that will include suggestions to work with elected officials. We suggest, if you have not done so, that you begin discussions with your government relations staff. Watch for advice on how to bear up and bear the responsibility of supporting or opposing what is being proposed.

The Department expressed concerns that for purposes of state authorization of distance education, Attorneys General in some reciprocity member states wish to protect their residents by enforcing their own, more stringent, state laws and are unable to do so under reciprocity.

Some negotiators originally proposed to allow states to enforce their own education-specific regulations. In response, some negotiators pointed out that some states have little to no oversight of out-of-state institutions.

To the suggestion that states are prohibited from enforcing these laws, a few negotiators also pointed out that states voluntarily joined the reciprocity agreement, most through state legislation signed by the governor, and are free to leave the agreement at any time if they disagree with the agreement.

Additionally, the Department proposed a revision to the regulation addressing the authorization of in-state institutions that was discussed and revised in week three.

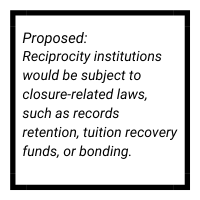

The Department proposed language around state enforcement of certain state laws regardless of whether or not the institution is participating in reciprocity. After several variations during negotiations, these three were the Department’s final proposed changes for States participating in a distance education reciprocity agreement:

Midway through the negotiations, the Department released proposed language that included that a reciprocity agreement must allow a state to enforce all applicable state laws. This proposal would have severely undermined reciprocity as state oversight and requirements would vary from state-to-state.

The final draft settled that a state can enforce its own general-purpose state laws (as is currently in regulation). These general-purpose state laws include fraud, misrepresentation, criminal acts, etc. This portion of the final proposed language is not a change to current requirements. A few negotiators were adamant that each state should be able to enforce all their rules. They envision reciprocity as merely having a single application and a single fee for all states. That would completely undermine reciprocity, but they will likely push the Department to adopt that position in the published proposal. The Departments’ representative pointedly told negotiators that the Department made concessions in negotiations that it might abandon if consensus was not reached. That was a stark reminder that the impact on reciprocity could, ultimately, be more stringent or damaging than what is reported here.

The Department’s language addressing state closure laws is a change but is consistent with the intent of the recently released final Certification Procedures regulations. However, that language is contrary to the current policy of the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA). The new proposed language would cause SARA to revise its policies to allow states to enforce their applicable state closure laws.

Finally, if an institution violates general purpose laws or regulations, the proposed language allows for any state to limit or revoke authorization through reciprocity in their state. In practice, this already exists in SARA as an institution that violates state laws will be reviewed by their home state with consequences that could affect their participation in SARA nationwide, not just in one state. However, this could result in unilateral state action not currently envisioned in SARA.

The importance of a transparent complaint process for reciprocity agreements was a priority of the Department beginning with the original issue paper released in January. The final proposed language focuses on four features that a reciprocity agreement complaint process must include.

While we know the proposed regulations are intended to apply to any state authorization reciprocity agreement that is developed, SARA provides many of these features already. The first three changes proposed by the Department are already in SARA policy. SARA promotes interstate communication about complaints, publishes quarterly complaint data, and allows states to enforce general-purpose laws. One minor difference is that SARA does not currently collect complaints by “type.” There is a proposal in SARA’s policy change process to require the classification of complaints. That proposal is likely to be accepted.

Another difference between the proposed and current SARA policy, is that the SARA policy directs the student to follow the institution’s complaint process before submitting a complaint to the State Portal Entity (SPE) where the institution is located (called the home state). The home state then will collaborate with the state where the student is located, but the home state maintains the final authority. The Department’s proposal recognizes that some states require the student to “exhaust” all grievance processes at the institution before submitting a complaint to the SPE. However, there could be very legitimate reasons a student would wish to address the state without going through the institution’s process.

Additionally, this proposed language suggests that the student could submit the complaint to the state where the student is located, and that state would have the authority to resolve the complaint. Under this proposed language, a state could enforce SARA policy on the out-of-state institution. However, we wonder about the enforcement of state law on an out-of-state institution that has no physical presence in the state. This also could result in State activity that is in conflict with current SARA policy.

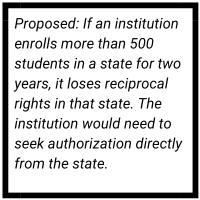

The Department’s proposed language would require that institutions that enroll more than 500 students in a state in the two most recently completed award years may not be authorized through reciprocity in that state. The institution must seek authorization directly from the state.

The basic premise of this proposal is that reciprocity was intended only for institutions with a small footprint in a state. A large number of enrollments increases the risk to the state and it should be more directly involved in overseeing those institutions. Institutions that serve more than 500 students in a state would be required to obtain individual state institutional approval in those states. Reciprocity would only be sufficient for state authorization in the states for which the institution serves fewer than 500 students. Some negotiators sought to set the number at 100 or 200 students in a state. We could see a lower number emerge in the published proposal. On the other hand, other negotiators suggested that there are better indicators of risk than an enrollment count. Smaller fly-by-nights might do more damage than established larger institutions.

This proposed language was only added in week three and, as a result, there was extremely limited discussion and there are many unknowns. Are students participating in experiential learning included in the 500 students? Whose data is being used? Can states provide institutional approval quickly enough for the institution to remain in compliance? Will there be extensions if the state cannot act in time?

And there is one noticeably big question. If an institution serves more than 500 students in a state that has no oversight of out-of-state institutions, how is this proposed language protecting students since it removes student consumer protections in reciprocity and replaces them with no protections?

The Department’s proposed language directs that a governing body for a reciprocity agreement must consist solely of representatives from state regulatory and licensing bodies, enforcement agencies, and the state attorney’s general offices.

The proposal intends to direct the composition of a governing board of a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is the entity administering the reciprocity agreement and places severe limitations as to those who may serve on the board including barring compacts who facilitate state collaboration to implement the agreement in their region. While it is understandable that states should fill the majority of the seats on a board administering a state-to-state agreement, the Department’s direction limits the ability to include subject matter experts to create sound policy. While we believe the SARA governance structure needs an overhaul that greatly prioritizes state voices, there remains a fundamental question of whether there is the legal authority for the Department to dictate the representation on a nonprofit organization governing board.

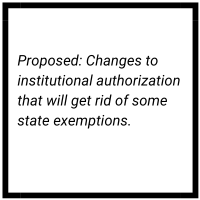

The Department also proposes revised regulations that could change what it means for the institution to be authorized in the state where the institution is located to be eligible to participate in Title IV HEA programs.

In addition to maintaining the 2010 requirement that a state must provide a process to accept and resolve student complaints and enforce state laws, the Department’s proposal revises the ability of the state to offer certain exemptions to state authorization of institutions located in the state.

Under the Department’s proposed regulations, states could only exempt:

Currently, states can exempt institutions based on accreditation or in operation for at least twenty years. Those exemptions would be sunsetted by July 1, 2030. Additionally, an institution would not be exempted if there has been a change in ownership.

The Department expressed concern that in the event of a closure, an institution that is not subject to state oversight because of an exemption would leave a student without protection. The final proposed language allows states to rely on their oversight of public institutions and community colleges as well as provide for the continuation of exemptions for long-standing private institutions. This proposed language was a concession by the Department offered late in the rulemaking negotiations.

The Department put forward a number of proposed regulations that would directly affect distance education including proposed regulations around taking attendance, Title IV eligibility for asynchronous clock hour programs, the creation of a virtual campus designation for distance education programs, and accreditation of institutions offering distance education.

When a student withdraws from a course or institution, the college or university needs to follow a complex set of rules to determine the amount (if any) of disbursed aid that should be refunded to the Department of Education.

If the student withdraws without official notice from distance education courses, the institution must determine the “last day of attendance,” which is defined as the last time the student participates in one of the activities identified as “active engagement” in the course. Examples include taking a test, submitting a paper, or participating in an online discussion about content. Simply logging into an LMS does not count. This determination of “last day of attendance” is a higher bar for online courses than what is required for in-person courses.

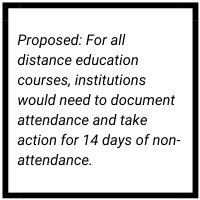

To begin negotiations, the Department cited some instances of institutions failing to adequately document the “last day of attendance” or knowingly adjusting the date to lower the amount to be refunded. The Department proposed the following to “simplify” and improve the accuracy of determining the student’s last day of course activity:

There was little discussion of this issue during negotiations other than trying to add additional exceptions. The Department said that this would “simplify” the process because institutions are already tracking all academic activities in their LMS. We talked to individuals from several institutions and we reached out to NASFAA (the financial aid organization) about the proposal. With the exception of fully-online institutions and those that are already attendance taking, all of those who responded agreed this would not “simplify” the process and would add more work. They also felt that they are aware of the “last day of attendance” requirement and are able to document it correctly. This regulation would result in more work to arrive at the same artifact that documents the student’s last activity.

Regarding the “14 day” requirement, we will need to clarify the Department’s intent. At one point they said that this would prompt the institution to follow-up with absent students and try to re-engage them. At another time, it sounded like a fixed deadline. Institutions will need to document excused absences for students who (for example) are known to be ill or on temporary military duty. Some institutional personnel said that with post-traditional students, it is common for students to not participate for two weeks (due to personal or work issues), but still complete the course successfully.

Although requested more than once by a negotiator, documentation of the extent of the non-compliance was not provided.

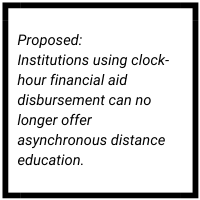

Most commonly, federal financial aid is disbursed to students either through the credit hour or clock hour method. The latter is commonly found in practical programs, such as cosmetology, welding, and the like. Aid for clock hour programs is, literally, determined by student participation by the minute. The Department expected that institutions using asynchronous distance education would have “sophisticated technologies” to track that activity. They reported several instances of weak time tracking. As a result, they proposed:

NOTE: This will NOT affect courses offered through credit hours.

At first, we and our friends at the American Association of Community Colleges had trouble finding affected programs. As negotiations went on, we were able to find more and more institutions that were shocked at the proposal. Negotiators tried a last-minute proposal to save funding for asynchronous clock-hour programs, but it was unsuccessful. We understand the Department’s concern but are afraid it will hurt students in these programs who demonstrate the most need. Requested data on the extent of the noncompliance was not provided. It was unclear why they would ban an entire modality without sharing convincing evidence.

Institutional accreditation agencies conduct “substantive change” reviews of institutions when certain benchmarks are reached. It is a logical check to make sure that the institution is acting within its mission and has the capacity to successfully implement new initiatives. The Department requires some “substantive change” reviews and the agencies could have additional requirements. In 2021, the Department of Education guidance charged accreditors with overseeing any program that is offered at a distance “in whole or in part.” The accrediting agencies struggled with this change as nearly every program across the country would trigger the need for this review. The Department proposed the return to a version of the pre-2021 standard without any objections from the negotiators:

This is an improvement over the current “in whole or in part” criterion, which accrediting agencies had trouble implementing. It is quite reasonable for an institution to be reviewed the first time it offers more than half of a program at a distance. Given the post-COVID world, we strongly believe that many institutions will trigger review by surpassing the second or third threshold. It will be interesting to see how accreditation agencies deal with this requirement as there will still be many, many institutional substantive change reviews as a result.

The Department also proposed to add the following definition (to go into CFR 34 600.2) that will help with these calculations and elsewhere in the proposed rules. Except for the part after the “or,” you might recognize this as the definition used by IPEDS. We were intentional in suggesting that the negotiators make this addition:

Distance education course: A course in which instruction takes place exclusively as described in the definition of distance education in this section notwithstanding in-person non-instructional requirements, including orientation, testing, academic support services, or residency experience.

Institutions are required to report students as participating in one of three physical locations: a) the main campus, b) a branch campus, or c) an additional location. The latter is a: “physical facility that is geographically separate from the main campus of the institution…at which the institution offers at least 50 percent of an educational program.” The Department adds to that last definition and also proposes the collection of additional data about distance education students:

Frankly, we are still trying to figure out the long-term implications. One benefit of the virtual location is that if an institution were to close its entire distance education operations, the affected students would have the same financial aid protections as if the entire institution closed. Additionally, we have long advocated for more collection of data about distance education programs and students. The Department said it will allow it to collect more data about distance education programs, as defined in that section. The other data requirement reported above is more granular as to enrollment in courses. We have many questions about the details about what will be gathered. We have all seen “research” and data analyses that fall short and pin differences in outcomes on the modality. They often overlook differences in the population served. This data can be quite helpful. It would be great to have regulations based on outcomes and not suppositions. Setting the context is important.

The Department also proposed numerous changes to Cash Management regulations associated with Title IV financial aid. Although most of those proposed changes are focused on financial aid processes that are outside the scope of WCET members, proposed changes to including instructional materials in tuition and fees, i.e., inclusive access programs, may impact your institutions.

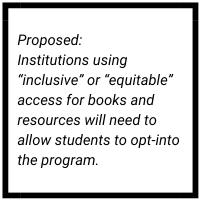

Some institutions bundle the cost for instructional materials into a student’s tuition and fees to lower the cost of books and materials as well as ensure that students have all of their instructional materials on the first day of class. The Department, citing a desire to ensure that students have direct control over how their financial aid is spent, proposed removing an institution’s ability to automatically bundle the cost of instructional materials into tuition and fees unless:

Although the Department had initially proposed regulations that would have allowed for a “health and safety” exemption, that exemption was removed in the proposed week three regulations. Under the final proposed regulations, the only exemption is for confined or incarcerated students.

If the proposed regulations go forward, institutions with opt-out inclusive access programs will need to convert the programs to opt-in. They will also have to show that the cost of the opt-in materials are at or below fair market value. It was unclear from the Department’s discussion how frequently this analysis would need to be conducted. The Department made clear that they greatly valued student choice in how they spend their financial aid and personal funds. Additionally, it does not appear that institutions with practical programs such as welding, cosmetology, or even scuba diving that require specific equipment will be able to bundle the cost of that equipment into tuition and fees. We recognize that may be problematic for programs that require specific equipment as a part of industry standards.

So, what’s next from the Department?

The Department will now work on the final proposed language that may differ from the language that was provided for the final week of negotiations. In fact, on at least one occasion the federal negotiator stated that there would be no guarantee that language negotiated during week three would be reflected in the Department’s final proposed language. Because there was no consensus on any of these issues, the Department can put forward whatever language it wishes.

Once the Department releases the final proposed regulatory language, it will be available for public comment for at least thirty days. Although we are not certain when the Department plans to release the final proposed rules, we have heard a credible rumor that it will be in May or June. Once the Department receives public comment, it must respond to those comments. If it can publish the final regulations by November 1 st , then they will go into effect on July 1, 2025. It’s possible that a few sections might have implementation dates beyond July 1 if the Department believes that institutions will need additional time to come into compliance. The Department divided its work into six “issue papers.” It is also possible that they may decide to release proposed regulations for some of those in the coming months and wait on the others.

In the coming days we will continue to keep our ears to the ground and talk with other stakeholders. Additionally, we will publish a call-to-action post in the coming weeks that will contain one-page issue summaries that you can share with your government relations and institutional leadership teams. We suggest that you begin working with your leadership and government relations teams to engage with elected officials if there are portions of these regulations that you either support or are against. Either way, consider the eventual impact that the proposals could have if implemented…on students, on states, and on processes to implement them. Think about what questions you need to have answered.

If the Department plans to publish proposed regulations for comment in May or June, we will have little time to act. Be prepared.